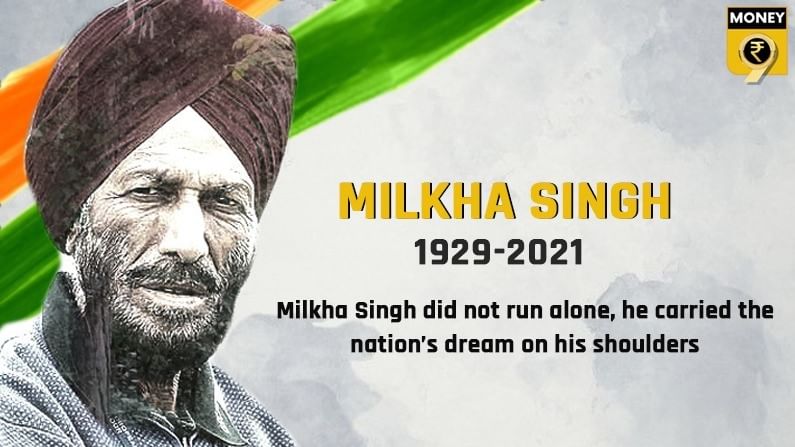

Milkha Singh did not run alone, he carried the nation’s dream on his shoulders

Milkha Singh was introduced to sprinting when he was serving in the Army and after a few years, the nation learnt to dream big

- Avijit Ghosal

- Last Updated : June 19, 2021, 19:11 IST

July 29, 1911: Barefoot footballers of Mohun Bagan defeated East Yorkshire Regiment to win the IFA Shield.

August 15, 1936: Barefoot and without a tooth that the German goalkeeper knocked off, Dhyan Chand led India to an 8-1 win over Germany in Berlin Olympics to humble the lion in its den.

September 6, 1960: In Rome Olympics, Milkha Singh missed a bronze by the narrowest possible 0.1 second but ignited Indian spirit for the first time in a track and field events in a global arena.

Bigger emotions

Sportsmen become great when they come to embody emotions that transcend the sport. When Mohun Bagan defeated the Englishmen, it unleashed a wave of patriotism that a million leaders could not have achieved though their fiery speeches. With his wily stick major Dhyan Chand trapped Germany to demonstrate that the artistry of a subjugated nation can vanquish muscle of a dominant white nation easily.

Milkha Singh kept up this tradition – he missed a medal by a whisker, but raised the dreams of a nation, left impoverished by two centuries of brutal colonisation, to excel in the thoroughly physical world of athletics.

Very few sportsmen snugly fitted into the overworked noun legend as Milkha Singh (November 20, 1929 – June 18, 2021) did.

Flying barefoot

He was called the ‘Flying Sikh’ because the nation wanted to fly with him.

It was symbolic of his country whose economy was in a shambles by the British and which was grappling with the challenge of proving food and shelter to an undernourished population.

But that was also the time when Singh learnt how to break free from the shackles. He used to work in the armed forces and perhaps the environment contributed to his steely resolve.

First Indian athlete

In the 1958 Commonwealth Games held in Cardiff, Milkha Singh won gold in the 440-yard sprint. He was the first Indian athlete to win a gold in the Commonwealth Games.

Singh, who clocked 46.6 seconds, defeated South African sprinter Malcolm Spence.

That was only 11 years after the country had become independent and the Commonwealth Games had not suffered a devaluation as it has suffered now.

New identity

His victory gave a struggling nation an identity and confidence in track and field events in which India was struggling to stay at the fringes.

Singh was one of the most successful athletes in Asia. In the 1956 Asian Games, he won gold in the 200 and 400 metres sprint. In the 1962 games, he won gold in the 400 metres — his favourite event and also in the 4X400 metres relay.

He also represented the country in the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne and 1964 Olympics in Tokyo.

A towering bridge

Behind that rugged frame Milkha nurtured a heart full of softness and sensitivity. Despite being a trailblazer who was receiving a lot of adulation, the wounds of Partition remained raw within him even as he conquered not only his ghosts but also his famed competitors. Such has been his sporting acumen that despite the arch rivalry between India and Pakistan made worse by bloody history, Milkha got his nickname ‘The Flying Sikh’ from a speech by General Ayub Khan after the race in Rome.

His fight and flight demonstrated his capability to bridge boundaries amidst great animosity and, most important, symbolised rare shared south Asian pride. Flying Sikh’s last journey for sure would breed a billion baby steps to clinch the marathon.

Rocky terrain

In a way, Singh’s tumultuous life prepared him psychologically for a battle that he waged all alone on the tracks.

He was born in Gobindpura, which is now in Pakistan. He was one of 15 children, eight of whom had died before the Partition. He suffered the loss of both parents in riots and displacement when the country was partitioned.

In his youth, he was imprisoned for travelling in a train without a ticket and his sister pawned her jewellery to secure his release from Tihar Jail.

Refugee camp

Singh also spent some time at refugee camps in Purana Qila and Shahdara in Delhi.

He could have drifted away into a lawless life but for his brother who prevailed on him to try for a place in the armed forces. He could get in after the fourth attempt in 1951.

Always a sturdy runner, apparently Singh had his first brush with athletics when he was stationed in Secunderabad. In his village Milkha would often run to school. The army spotted this natural gift after he finished sixth in a compulsory cross-country and encouraged him for training.

Morale booster

It is believed that before the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru himself had a word with Singh to persuade him to keep aside his memories of Partition and compete against Pakistani athlete Abdul Khaliq.

If Singh ever lamented a moment, it was perhaps his slowing down midway in the 400-metre sprint and looking towards his competitors. Still then, he broke the Olympic record in that race.

Following his show in 1958 Commonwealth Games, Milkha Singh was promoted from a sepoy to a junior commissioned officer. In 1998, he retired from service as the director of sports in the education department of the government of Punjab.

He was conferred the Padmashree. In 2001, he spurned the Arjuna Award on the ground that it was to encourage young talents.

But none of these are an actual measure of Singh’s success.

Great teacher

His real success was the ability to instil confidence and resolve among his countrymen that they could be good athletes, an area where Indians had a disadvantage on two counts – genetic, especially compared to those of African origin, and poor infrastructure of a struggling and resource-scarce nation.

Great battles are perhaps always waged alone. The image of an individual soldering along alone works wonder with the spirit of a nation. That’s why Bobby Fischer’s rise against the mighty Soviet chess machine was such a toast for the Americans.

In a way, he had similarities with another icon African-American Jesse Owens, who landed a resounding slap on the face of a white supremacist Hitler by winning four golds in the 1936 Berlin Olympics with a world record in the 4X100 metres relay.

Second-to-none symbol

Milkha Singh was no less rich in symbolism. When he grew up as an athlete, there was virtually no sporting infrastructure in the poverty-stricken society where he was trying to perfect a difficult art. The armed forces could hardly offer him what his rivals in Europe or the US would train with. And unlike today, training in a foreign land was not heard of in those times.

Sprinting has always been a super-specialised area of sport where there are no retakes and fortunes are decided on the basis of tens and hundredths of a second. Milkha had only his resolve that was tempered and hardened in the rough terrain of his native village to run on.

Milkha knew what he was up against. While he had almost nothing to fall back on, he had to bear the expectations of a young independent nation eager to discover a hero in the field of sports.

And he delivered spectacularly. with His fourth-place timing of 45.73 seconds was a national record for the country for about 40 years.

Love and accolades

Fortunately, Milkha was not one of those who lived unrecognised. People loved him, respected his achievements though not always fully aware of their far-reaching implications.

In 2013, when people were addicted to abridged entertainment – the T20 championship began at least six years earlier – his biopic Bhag Milkha Bhag that ran for 3 hours 9 minutes, ran to packed houses all over the country and none complained about it being a drag. It netted Rs 210 crore.

Needless to say, none was watching Farhan Akhtar. Everybody was trying to live the times Milkha ran into history.

But Milkha never ran alone. He carried his nation’s dream on to his shoulders. Wrong. He taught the nation to dream in the tough world of track and field.

Download Money9 App for the latest updates on Personal Finance.

Related

- मैक्सिको के 50 फीसदी टैरिफ पर सरकार ने शुरू की बातचीत; जल्द समाधान की उम्मीद

- इंडो- US ट्रेड डील में पहले हट सकती है पेनाल्टी, रिपोर्ट में दावा

- रुपये ने फिर बनाया ऑल टाइम लो, जानें क्या है वजह

- बैंक कस्टमर के लिए बड़ी खबर, RBI हटाएगा ओवरलैप फीस,

- मैक्सिको ने अपनाई US जैसी पॉलिसी, 1400 से ज्यादा प्रोडक्ट लगाया भारी टैरिफ

- SpiceJet विंटर सीजन में जोड़ेगी 100 नई फ्लाइट्स! Indigo के कटे रूट्स का करेंगी भरपाई